skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Article: Oil, Cash and Corruption

Oil, Cash and Corruption

New York Times

November 5, 2006

By RON STODGHILL

ON a warm afternoon in late September, Nursultan A. Nazarbayev strode across the tarmac at Andrews Air Force Base to board his private 767. Surrounded by an entourage of security guards and political advisers, Mr. Nazarbayev, the president of Kazakhstan, was heading home after an eventful visit that included a meeting with President Bush in the White House and a boating jaunt in Maine with the president’s father, George H. W. Bush. He also attended a swank fete at the Capital Hilton Hotel where his hosts, the business mogul Ted Turner and former Senator Sam Nunn, praised him for closing a major nuclear test site.

Warm welcomes aside, human rights groups frequently characterize Mr. Nazarbayev as a dictator who, during 15 years of rule, established a hammerlock on his country’s oil riches and amassed a fortune at the expense of an impoverished citizenry. Supporters say he has wedded a draconian political order to clear-eyed economic policies, making his country hospitable to foreign investment. But his White House visit came at a tender moment. About a month earlier, the Bush administration introduced its National Strategy to Internationalize Efforts Against Kleptocracy, an initiative aimed at preventing public graft worldwide by, among other things, denying corrupt leaders access to the United States financial system.

“Kleptocracy is an obstacle to democratic progress, undermines faith in government institutions and steals prosperity from the people,” President Bush said. “Promoting transparent, accountable governance is a critical component of our freedom agenda.”

Mr. Nazarbayev’s visit, coming on the heels of those sentiments, sparked renewed criticism of his leadership and questions about the White House’s dedication to battling corruption overseas — possibly explaining why the administration decided against holding a state dinner in the Kazakh leader’s honor. But behind the scenes, a legal drama has been playing out that analysts say may more fully explain why Mr. Nazarbayev and the White House are engaged in such an elaborate form of political kabuki.

In February, the United States attorney’s office in Manhattan is scheduled to go to trial in the largest foreign bribery case brought against an American citizen. It involves a labyrinthine trail of international financial transfers, suspected money laundering and a dizzying array of domestic and overseas shell corporations. The criminal case names Mr. Nazarbayev as an unindicted co-conspirator. The defendant, James H. Giffen, a wealthy American merchant banker and a consultant to the Kazakh government, is accused of channeling more than $78 million in bribes to Mr. Nazarbayev and the head of the country’s oil ministry. The money, doled out by American companies seeking access to Kazakhstan’s vast oil reserves, went toward the Kazakh leadership’s personal use, including the purchase of expensive jewelry, speedboats, snowmobiles and fur coats, federal prosecutors say.

Beyond the large amounts of cash involved and the top-flight access such sums often secure, the case against Mr. Giffen has opened a window onto the high-stakes, transcontinental maneuvering that occurs when Big Oil and political access overlap — a juncture marked by intense and expensive lobbying, overseas deal-making and the intersection of money, business and geopolitics. It is a shadow world of nebulous boundaries that people like Mr. Giffen establish and define, often on the fly. The case also illustrates the government’s struggle to reconcile its short-term energy interests with its longer-term political goal of encouraging democracy in countries the international community has deemed corrupt.

To be sure, many an American president has entertained a foreign leader under a cloud of suspicion, but Mr. Nazarbayev’s role in a federal criminal investigation makes him an unusual entry into that company. Bush administration officials have acknowledged that the Kazakh government falls short in its democracy-building efforts. But some foreign policy specialists see Kazakhstan as an important ally in the administration’s campaign against terrorism and a bountiful alternative to oil reserves in the volatile Persian Gulf — all of which promise to make the opening of the Giffen trial more than just hit-and-run bribery fare.

“The administration is naturally reticent about Giffen’s case,” said Raymond W. Baker, an energy policy analyst on loan to the Brookings Institution, a liberal research group. “It would probably be a lot easier on everyone if he had gotten away with it.”

IN a world long accustomed to outsize public corruption, some analysts say Mr. Nazarbayev is in a class by himself. “I can’t think of a leader in the free world as notoriously corrupt as Nazarbayev,” said Jonathan Winer, a former deputy assistant secretary of state during the Clinton administration. “We’ve known about his corruption for at least 15 years because our own intelligence agencies have told us.”

Mr. Nazarbayev is certainly a mixed bag of goods, others said, but that is the way the world works. As Jerry Taylor, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, a libertarian research group, put it, “Kazakhstan’s human rights record may be checkered, but if the United States were to disengage from those countries with checkered human rights and other bad actors, we’d be history.”

The Clinton administration itself embraced Kazakhstan in the 1990s and praised Mr. Nazarbayev for leading his country toward economic and democratic reform. Administration officials, including the former Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright, also met with Mr. Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan.

“The Clinton administration certainly had enough information about Nazarbayev’s corruption,” Mr. Winer said. “The information on him was open, notorious and present.”

The work of defending the curious financial and diplomatic portfolio of Mr. Giffen is the job of William J. Schwartz and Steven M. Cohen, of Cooley Godward Kronish in Manhattan. The firm’s 48th-floor conference room offers some of the standard accoutrements of the white-collar defense bar — handsome wood paneling, a flat-screen television, a skyline view facing south toward Wall Street and a long oval table surrounded by leather chairs and punctuated at its center by a bouquet of sharpened white pencils.

In the spring of 2003, federal agents arrested Mr. Giffen as he and Mr. Schwartz prepared to board a flight from New York to Paris. Prosecutors accused him of overseeing a tangled bribery network in the 1990s designed to buy access and influence in Kazakhstan for oil giants like Exxon Mobil, BP Amoco (now BP) and Phillips Petroleum (now ConocoPhillips). The payments, prosecutors said, violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which forbids American citizens or corporations from paying bribes to foreign officials to obtain business. None of the oil companies have been accused of any wrongdoing.

While Mr. Giffen’s lawyers have conceded that their client shuffled money from one secret bank account to another, they have maintained that he did not act alone. “Mr. Giffen was working with the knowledge of our government,” Mr. Schwartz said. “Jim’s access in Kazakhstan was a function of a bizarre historical time.”

At the heart of Mr. Giffen’s defense is a motion filed by his lawyers in June 2004 to Judge William H. Pauley III of Federal District Court in Manhattan, seeking access to classified government documents for his defense.

For now, each of the names, titles, and government affiliations of individuals mentioned in the document are blacked out on virtually every page. Mr. Giffen’s lawyers have argued that much of the evidence necessary to prove his innocence rests with various officials and agencies that helped him conduct business in Kazakhstan. Without such witnesses, the lawyers say, it will be difficult for them to prove their client was performing his duties as an American. Court filings by Mr. Giffen’s lawyers suggest that senior officials at the Central Intelligence Agency, State Department and White House encouraged him to use his close ties with Kazakh leaders to ferry valuable intelligence back to the United States. Judge Pauley has written an opinion supporting the motion, but the United States attorney’s office has appealed it.

“Before this is over, Giffen’s lawyers will file a variety of motions to get at the classified stuff, but the history of that isn’t terribly terrific,” said Jack Blum, a former investigator for the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee. “Senior officials can very conveniently avoid governmental embarrassment by keeping everything classified.” Mr. Blum added, “When you have a kind of blink-and-nod, clandestine waiver of the law with the government, once the problem blows up, you’re going to get hung out to dry.”

Spokeswomen from the C.I.A. and the White House declined to comment.

Congress passed the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in 1977 after concluding that bribery abroad had become an important foreign policy issue that “embarrasses friendly governments, causes a decline in foreign esteem for the United States and casts suspicion on the activities of our enterprises, giving credence to our foreign opponents.”

Mr. Giffen’s lawyers say he cannot be found guilty of bribing a foreign government because his activities were part of his official duties as an adviser to the Kazakh government and they received the blessing of senior American officials who regularly debriefed him on his activities.

That contention has prompted a blizzard of motions, memorandums and filings between the federal government and Mr. Giffen’s lawyers. Federal prosecutors have sought to block Mr. Giffen’s access to documents on the grounds that disclosing them could breach national security interests.

It was not only individuals in Kazakhstan who received some of their client’s bounteous fees, former associates of Mr. Giffen said. In 1998, two years before federal investigators began looking into Mr. Giffen’s activities in Kazakhstan, he invited Mark Siegel, a Washington political consultant, to join a group of policy experts to develop a blueprint for reforming Kazakhstan’s economy and government. It was an ambitious task, Mr. Giffen conceded, but its participants would be well compensated. Mr. Siegel, a former executive director of the Democratic National Committee, agreed to a monthly retainer of $30,000 for his firm and soon found himself on a flight to Almaty, Kazakhstan’s former capital.

As it turned out, Mr. Siegel was in high-powered company. Mr. Giffen had harnessed prominent businessmen, policy experts, lobbyists and former government officials to serve on the committee. Among those included in the group were Robert Blackwill, a former ambassador during the first Bush presidency, and Philip D. Zelikow, now a counselor to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Mr. Siegel recalled in an interview. Neither Mr. Blackwill nor Mr. Zelikow responded to interview requests.

“We were a kind of a Great White Hope,” Mr. Siegel said. The committee was divided into a “P Group” and an “E Group” to distinguish political and economic experts in the group. Mr. Nazarbayev “came across as a reformer open to free markets and fair elections.”

According to his lawyers, Mr. Giffen, at Mr. Nazarbayev’s direction, paid several million dollars in fees from Swiss accounts — many of the same accounts named in Mr. Giffen’s indictment — to committee members for their expertise on a range of policy issues involving Kazakhstan.

The group’s recommendations can be found in two spiral-bound documents that came to be known simply as the Red Books. Mr. Giffen’s lawyers, as well as Mr. Siegel, said the creation of the committee reflected Mr. Giffen’s interest in helping Mr. Nazarbayev move his country away from an authoritarian government to a more democratic model. While the Red Books lists an impressive array of financiers and policy makers in its membership ranks, some of those named in the document said they never worked with Mr. Giffen. One of those people, John C. Whitehead, the former chairman of the investment banking giant Goldman Sachs, acknowledged being an acquaintance of Mr. Giffen but said he was never part of the group. “I’ve never been to Kazakhstan,” Mr. Whitehead said, “and I’ve certainly not had that kind of formal relationship with Jim Giffen.”

Mr. Giffen’s lawyers declined to discuss any other aspects of his work with the committee, but said that the committee’s existence proved that the scope of his influence with policy makers far transcended energy matters.

SUPPORTED or not by the federal government, Mr. Giffen reportedly managed to orchestrate what the government describes in its indictment as an elaborate money laundering and tax fraud scheme carried out in six separate oil transactions from 1995 to 1999, all of which involved defrauding the government of Kazakhstan. Mr. Giffen is accused of hiding some of the proceeds in each of the deals through a series of wire transfers that ultimately landed in Swiss bank accounts. One deal Mr. Giffen’s indictment details involved Mobil Oil’s 1996 purchase of a 25 percent interest in Kazakhstan’s Tengiz oil field. Located in the mineral-rich Caspian region, Tengiz is the sixth-largest oil field in the world, producing 285,000 barrels a day, or about a third of the country’s daily production.

The indictment states that after Mobil paid Mr. Giffen a $51 million fee for negotiating the deal, he transferred half of the money to a Swiss account and then sent the money on a circuitous path through a number of other accounts, including one registered to a British Virgin Islands company. Exxon and Mobil merged in late 1999 to form Exxon Mobil, the world’s largest oil company. Russ Roberts, an Exxon spokesman, said Mobil was not the source of any payments to Mr. Giffen.

“Exxon Mobil has no knowledge of any illegal payments made to Kazakh officials by any current or former Mobil employees,” Mr. Roberts wrote in an e-mail response to an interview request. “We also have no knowledge of any illegal payments received by any current or former Mobil employees.” Mr. Roberts said neither Mr. Giffen nor his company, Mercator, had represented Mobil or Exxon Mobil.

In 2003, a former Mobil manager pleaded guilty to evading taxes on $7 million he received from Mr. Giffen starting in 1993. Mr. Roberts noted that Mr. Giffen’s payments to the manager had begun several years before any Mobil acquisition in Kazakhstan and that Mobil had not been the source of the payments. Although prosecutors described the payments to the manager as “kickbacks” for work done on Mobil’s behalf, the manager, Mr. Roberts said, repudiated that accusation. Mr. Roberts declined to further discuss the matter.

But according to the indictment, Mr. Giffen wired another chunk of what court papers describe as a Mobil fee, about $20 million, into another pair of Swiss accounts. Nurlan Balgimbaev, the former prime minister and oil minister of Kazakhstan, controlled one of the accounts, according to the indictment. A Liechtenstein trust, of which Mr. Nazarbayev and his family were beneficiaries, controlled the other account, the indictment asserts.

In the process, the government asserts, Mr. Giffen paid $36,000 of Mr. Balgimbaev’s personal bills for the upkeep of a house in Newtown, Mass., spent $30,000 to buy fur coats for Mr. Nazarbayev’s wife and daughter and bought a Donzi speedboat as a gift from Mr. Nazarbayev to Mr. Balgimbaev.

ConocoPhillips and BP, two of the other oil companies which the indictment says paid Mr. Giffen, declined to comment. A lawyer and former federal prosecutor who represents the Republic of Kazakhstan, Reid H. Weingarten, declined to discuss the case. But few involved on either side of Mr. Giffen’s case have denied that his ties to Mr. Nazarbayev were substantial, longstanding and gilded.

“Everyone agrees on one thing, which is that Nazarbayev took bribes,” said Rinat Akhmetshin, director of the International Eurasian Institute, a Washington research group that supports Mr. Nazarbayev’s political opponents. Mr. Akhmetshin said the case was being closely followed in Kazakhstan and that Mr. Nazarbayev’s political future could turn on the trial’s outcome. “The moment Giffen goes to jail, Nazarbayev is finished as a politician,” he said.

JAMES GIFFEN’S financial ascent — from a young banker on the make into a well-heeled political insider with a bodyguard, a chauffeur-driven Mercedes-Benz and a Kazakh diplomatic passport — was a serendipitous blend of lucrative financial opportunities in Eastern Europe and Central Asia and old-fashioned elbow grease.

The son of a clothier in Stockton, Calif., Mr. Giffen, who is now 65, had ties to the Soviet Union dating back to the early 1970s. After graduating from the University of California, Berkeley and the School of Law at U.C.L.A., he started his career at a minerals trading firm before joining a subsidiary of the Armco Steel Corporation (later acquired by AK Steel). Armco was led by C. William Verity Jr., a champion of increased trade with the Soviet Union who would later serve as commerce secretary in the Reagan administration. Mr. Giffen became a vice president at the Armco subsidiary, which sold drilling equipment to the Soviet Union.

Although Mr. Giffen did not speak Russian, and the Soviets showed little interest at the time in trading with the West, he persistently courted Russia’s leaders. Nattily dressed and with a cigarette constantly in hand, Mr. Giffen exuded an affecting bluster and self-assurance — many who know him call it bravado — that eventually gained him the ears of high-ranking Soviet leaders. By the mid-1980s, Mr. Giffen had left Armco and founded his own company, Mercator, a boutique merchant bank headquartered in New York. He began the company with a five-year contract from Armco and a board of directors that included Mr. Verity and two former government officials.

Over the next decade, his lawyers have said, Mr. Giffen came to count Mikhail Gorbachev in his network of powerful friends within the Soviet government, the Communist Party and the K.G.B. In the late 1980s, Mr. Giffen convinced Chevron, Eastman Kodak, Ford Motor and RJR Nabisco to form a coalition aimed at penetrating the Soviet market through joint ventures — deals that Mercator would handle.

Although that initiative collapsed with the Soviet Union in 1991, Mr. Giffen had apparently become a conduit for information involving United States-Soviet affairs. On one occasion, the White House asked him to describe a meeting he had had with Mr. Gorbachev and to suggest trade issues that the first President Bush should raise with Mr. Gorbachev, according to filings in the federal court case. A memo, which an American official apparently prepared for the first President Bush, recounts Mr. Giffen as stating the president had “hit paydirt” with Mr. Gorbachev and that “whatever President Bush wants to do, Gorbachev will try to do.”

When 15 independent states emerged from the collapse of the Soviet Union, Mr. Nazarbayev contacted Mr. Giffen, his lawyers say. Mr. Nazarbayev, head of Kazakhstan’s Communist Party, and Mr. Giffen, who was president of the U.S.-U.S.S.R. Trade and Economic Council, had become close friends by that time, said Mr. Schwartz, the lawyer.

DURING Chevron’s discussions to acquire an interest in the Tengiz oil field, the company became one of Mr. Giffen’s clients. The company says the relationship was short-lived. “In the early 1990s, Chevron obtained the services of Mr. Giffen with respect to business opportunities with Russia and the individual republics,” the company said in an e-mail response to an interview request. “Chevron terminated that relationship in 1992.”

Mr. Nazarbayev asked Mr. Giffen to play an advisory role within the newly sovereign nation of Kazakhstan, according to Mr. Giffen’s lawyers.

As the country’s first president, Mr. Nazarbayev was determined to attract the involvement of multinational oil companies in developing his country’s bountiful oil fields, according to political and economic analysts. To that end, Mr. Nazarbayev hired Mr. Giffen to serve dual roles. As a special adviser to Kazakhstan, Mr. Giffen oversaw the country’s efforts to attract investment from the United States, while his company, Mercator, advised the Kazakh government on oil and gas transactions.

“Giffen was able to cast himself as a bigger-than-life figure who really knew how to work the West,” said Martha Brill Olcott, a specialist on Central Asian and Caspian affairs with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “Nazarbayev liked that and they created a relationship of great personal trust.”

Mr. Giffen’s and Mr. Nazarbayev’s close relationship sparked resentment among some senior Kazakh officials. “The biggest problem with Giffen was that he was trying to create an instrument of government that would keep himself and the president in power,” said the former prime minister of Kazakhstan, Akezhan Kazhegeldin. “He never dreamed he’d be so close to power.”

In a telephone interview, Mr. Kazhegeldin declined to discuss Mr. Giffen’s indictment but said that he and Mr. Giffen had clashed on several occasions. Within Kazakhstan’s senior ranks, Mr. Kazhegeldin had gained a reputation as a champion of free enterprise economics and someone favored among Western leaders, Ms. Olcott said. Mr. Kazhegeldin himself asserted that his penchant for economic reform and his calls to reform his country’s autocratic government ultimately alienated both Mr. Giffen and Mr. Nazarbayev.

Now living in Italy and London, Mr. Kazhegeldin said he had spent millions of dollars on lobbyists and public affairs specialists in the hope of defeating Mr. Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan’s next election, scheduled for 2011. “There is a small group of people getting rich — and I mean really rich — in Kazakhstan while the rest of society remains really poor,” Mr. Kazhegeldin said. “The leadership is not interested in pushing a market economy. They keep two sets of books, one for themselves and another for everyone else.”

Mr. Kazhegeldin, however, is a veteran of the pell-mell economic scramble of the post-Soviet years. He amassed his wealth as a rogue salesman in the waning years before the Soviet Union’s dissolution, selling scrap metal on the black market while studying international business at Moscow’s K.G.B. Academy, according to a résumé furnished by a close associate who asked not to be identified because of the nature of the work he does for Mr. Kazhegeldin. After the spy school kicked him out in 1989 for his moonlighting activities, Mr. Kazhegeldin went on to make his millions exporting chemical fertilizer, the associate said.

Mr. Nazarbayev began his own investigation of Mr. Kazhegeldin’s finances in the fall of 1998 — to score political points, Mr. Kazhegeldin’s supporters said — which snowballed into an international scandal when it led the United States government to examine Mr. Giffen’s activities more closely.

In fall 1999, the Kazakh government accused Mr. Kazhegeldin of embezzling several million dollars into an offshore account that he controlled. Mr. Kazhegeldin denied any wrongdoing and said neither he nor any family members had access to the account.

Mr. Kazhegeldin accused Mr. Nazarbayev of arranging the deposit and leaking information about it to the news media to secure victory in a 1999 presidential election. A 1999 State Department examination of the Kazakh investigation into the accounts reportedly linked to Mr. Kazhegeldin concluded that the investigation, “while possibly grounded in facts, appeared motivated politically.”

After Kazakh officials contacted Belgian and Swiss authorities to examine Mr. Kazhegeldin’s possible role in the looting of government funds, the Swiss contacted the Justice Department to discuss what appeared to be a pattern of questionable transactions between Kazakhstan and American and European oil companies.

As federal investigators reviewed the transactions in 2000, they noticed that Mr. Giffen was party to many of them, according to his lawyers. Over the next two years, investigators focused more closely on Mr. Giffen and subpoenaed records from Mercator. A treaty between the United States and Switzerland permitted investigators to obtain detailed records of Mr. Giffen’s financial activities in New York and Switzerland, according to his lawyers. In February 2003, the United States attorney’s office in Manhattan won a grand jury indictment against Mr. Giffen on fraud charge. A month later, as Mr. Giffen boarded a flight from New York to Paris with his lawyers, federal authorities arrested him.

As the Giffen trial moves forward, with the possibility that more information about Mr. Giffen’s interactions with the Kazakh government, Washington policy makers and multinational corporations may emerge, it promises to shine a spotlight on the terms of engagement when the United States courts resource-rich countries riddled with corruption.

“Corruption is at the heart of what causes poverty in third world countries,” said Mr. Blum, the former Congressional investigator. “We tell ourselves that in the short term, we can buy these guys who will serve the national interest, but in the long run it always turns into a disaster.”

The World Bank, the Washington economic development organization that focuses its efforts on needy countries, has brought much of the current debate about overseas financial corruption to the fore. In the early 1990s, the bank started measuring corruption within the governments of its member countries. The initiative was controversial because until then, economists had largely considered corruption to be an ethical or cultural issue. The bank began interviewing hundreds of private citizens, as well as employees in government and business, trying to pin down the pattern and prevalence of corruption in areas like banking, real estate, health care, media and education.

“What we realized was that corruption is not just a moral or ethical issue but an economic development issue,” said Daniel Kaufmann, an economist who began the World Bank’s corruption studies. “We estimated that with good governance, there is a threefold increase in per capita income as funds that should be allocated toward the gross domestic product are not siphoned off.”

BY 1995, Mr. Kaufmann’s team developed a rating system that measured factors like corruption control, absence of violence, government accountability and regulatory quality in various countries. The ideas became a cornerstone of the bank’s agenda. Since the mid-1990s, it has started more than 600 anticorruption programs in nearly 100 countries. Under Paul D. Wolfowitz, who became head of the World Bank last year, it has continued its anticorruption efforts. In what Mr. Wolfowitz described as efforts to stem corruption, he recently threatened to cut loans and development contracts in India and Kenya. Mr. Wolfowitz, a former deputy defense secretary in the Bush administration and an architect of its policies in the Middle East, has received the White House’s backing in prioritizing anticorruption campaigns. But some research groups, and some of the bank’s own administrators, have criticized Mr. Wolfowitz for using the World Bank to advance the White House’s foreign policy goals in countries like Iraq, where the bank recently increased its lending support.

A World Bank spokesman denied that Mr. Wolfowitz was serving the White House’s interests. “He doesn’t hesitate to serve as an independent voice for the poorest people — including when it goes against the grain on issues like trade, debt relief and support for official development assistance,” the spokesman wrote in an e-mail message.

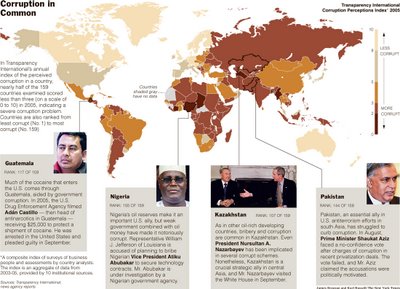

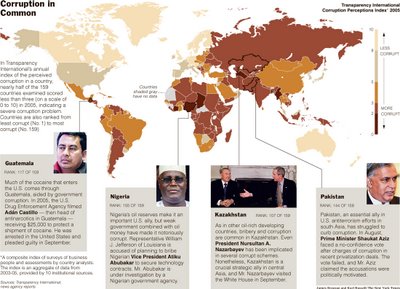

Kazakhstan, and Mr. Nazarbayev’s stewardship of the country, have been fodder for World Bank scrutiny. According to the bank’s 2005 Worldwide Governance Indicators, Kazakhstan ranks with Angola, Bolivia, Kenya, Libya and Pakistan among the world’s corruption hotspots.

Other anticorruption watchdogs, like Transparency International, also rate Kazakhstan poorly for its governance practices. The State Department’s 2005 Kazakhstan Country Report on Human Rights Practices noted that the Kazakhstan government’s “human rights record remained poor” and that “corruption remained a serious problem.”

Despite such low scores and scathing critiques, the World Bank has lent Kazakhstan more than $2 billion for 28 projects since 1992. In fiscal 2006, commitments to Kazakhstan totaled $130 million, with overall commitments for active projects at $648 million.

Juan José Daboub, who oversees the World Bank’s governance program, declined to comment specifically on corruption issues in Kazakhstan or on Mr. Nazarbayev’s leadership.

“We respect what countries pick in terms of leadership,” said Mr. Daboub. “We are not judges, prosecutors or investigators.”

But Mr. Baker, the energy analyst at the Brookings Institution, saw things differently: “If you’re a country with a lot of oil, you get a lot of free passes.”

Human rights groups have spent years blasting Mr. Nazarbayev for shutting newspapers critical of his regime; passing laws that threatened to prosecute individuals whose actions were considered threats to the country’s economic development efforts; tolerating and participating in vast graft; and the like. But rarely have American policy makers openly opposed Mr. Nazarbayev’s leadership and actions, analysts said.

“He has done a pretty sophisticated job of reaching out to many sectors,” said Thomas O. Melia, deputy director of Freedom House, a liberal research group in Washington. “He is not like a lot of leaders, who put all of their eggs in the White House basket.”

Even so, the White House, through successive administrations, has been a reliable and enormously influential ally of Mr. Nazarbayev, and its continued embrace of Kazakhstan’s leader rankles some members of Congress.

“It’s just hypocritical for President Bush to issue statements on combating foreign corruption and then to embrace a dictator,” said Senator Carl Levin of Michigan, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee. “It sends a real negative message to countries that you’re trying to win support from.”

Senator Levin characterized Mr. Nazarbayev as “an iron-fisted dictator who imprisons his opponents, bans opposition parties and controls the press.”

But some say the White House should be worldly wise when it comes to supporting certain countries in volatile but resource-rich regions. Ariel Cohen, a senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative research group, said the Bush administration had effectively balanced its long-term foreign policy goals involving energy issues with its human rights standards in Central Asia. Because of turmoil in other Central Asian countries, Kazakhstan has emerged as a possible military foothold for the United States there.

“When it comes to Kazakhstan, it’s all about three things; energy, democracy and security,” Mr. Cohen said. “I would argue that relative to his competition in Central Asia, Nazarbayev is the most successful in pursuing each of them. Sure, there is still corruption and insufficient rule of law, but this is a country that 15 years ago had no statehood. They have started from scratch.”

If Mr. Giffen’s trial gets under way in February, it may enrich and shed light on the debate about the United States’ engagement with Kazakhstan and other countries that have poor anticorruption records.

FOR their part, Kazakh officials worry that Mr. Giffen’s trial may set their nation on a backward course. Mr. Weingarten, the lawyer representing the Kazakh government, wrote a letter in 2002 to the Justice Department on behalf of his client. The letter was straightforward: “Even if it were possible for the prosecutors to indict President Nazarbayev, we cannot envision a scenario where the United States would deem it in its interest to indict the leader of an important strategic ally.”

Even more important, said some of Mr. Giffen’s allies, is that the whole messy affair of moving bribes and laundered money around the world has caused Mr. Giffen’s work to become unfairly mischaracterized.

“If this whole thing was just about oil, it was one of the biggest snow jobs in U.S. history,” said Mr. Siegel, the Washington lobbyist who aided Mr. Giffen’s efforts in Kazakhstan. “I believed that we were doing God’s work.”

No comments:

Post a Comment